Conceptual Paradigm To Understand Male College Students: Integrating the Psychology of Men and Chickering and Reisser’s Identity Vectors

In this file, the theory in the psychology of men are integrated with Chickering and Reisser’s identity vectors with a single conceptual paradigm. This conceptual paradigm represents a new way to understand college men in the student development literature. Furthermore, the paradigm provides a conceptual framework to make a call to action for comprehensive campus programming for men.

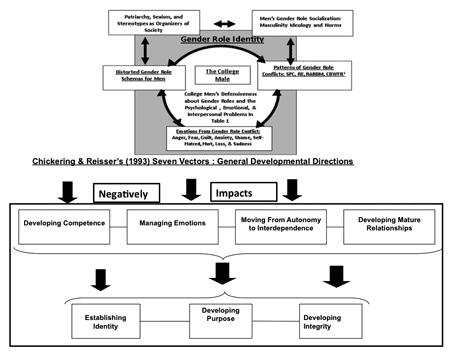

Figure 1 shows 6 conceptual areas from the psychology of men that are theoretically related to college men’s gender role identity and Chickering and Reisser’s 7 identity vectors shown at the bottom of the paradigm.

Figure 1: A Conceptual Paradigm Explaining College Men’s Gender Role Conflict Impacting Seven Developmental Vectors

[click image for a larger version]

1SPC = Success, Power, Competition; RE=Restrictive Emotionality; RABBM=Restrictive Affectionate Behavior Between Men; CBWFR = Conflict Between Work and Family Relation

The directional and bi-directional arrows in Figure 1 imply complexity with college men’s masculinity dynamics and require thinking outside of the status quo’s view of college student development. Each arrow implies possible educational programming possibilities as well as empirical research on college men.

At the top of the conceptual paradigm, the larger patriarchal society, sexism, and stereotypes are shown as organizers of society. Patriarchy instills sexist values and stereotypes that influence how men relate women, other men, and themselves. With society organized this way, it is not surprising that men come to campus with distorted or ambivalent view of masculinity, femininity, and themselves. In the top-right corner of Figure 1, men’s gender role socialization and specifically, the masculinity ideology and norms are shown. As documented earlier (See Table 1), narrow, rigid and sexist masculinity ideologies represent significant emotional and interpersonal problems for boys and men.

Gender-role identity, construed as a subset of Chickering and Reisser’s overall notion of human identity, is shown as the dominant issue for college men. All six of the conceptual areas impact college men’s gender role identity. Gender role identity is the “Who am I, as a man?” question that consciously or unconsciously emerges during adolescence and the college experience. Gender role identity is formed by many factors, but the patriarchal system and men’s socialization in families and schools are significant contributors. Masculine gender-role identity is defined as a man’s total conception of his masculine roles, values, functions, expectations, and belief system (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). This includes how biological sex, social learning, and stereotypes of masculinity and femininity shape the man’s sense of self over the lifespan. Masculine gender role identity is everything that the man says and does that communicate his masculine and feminine dimensions. Men have both a conscious and unconscious aspect of their masculine gender role identities. Consequently, coming to terms with masculine identity can be difficult, elusive, and confusing. This makes campus programming for men critical and an important part of student affair’s mission.

Gender role identity is continually shaped by the many interacting and socializing dynamics shown in the paradigm. Distorted gender-role schemas develop from masculinity ideologies and norms learned in our sexist society. Distorted gender-role schemas are exaggerated thoughts and feelings about the role of masculinity and femininity in a man’s life. Boys and men internalize these distortions when they learn stereotypes of restrictive masculinity ideology from society, in families, and from peers. Distortions occur when a man experiences an intense pressure to meet stereotypic notions of masculinity and prove his masculinity (Kimmel, 2003). This results in fears and anxieties about not measuring up to traditional gender-role expectations (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999).

On the right side of Figure 1, the four patterns of GRC are shown including Success, Power, and Competition (SPC), Restrictive Emotionality (RE), Restrictive Affectionate Behavior Between Men (RABBM), and Conflict Between Work and Family Relations (CBWFR). Rresearch provides strong evidence that these patterns of gender role conflict are related to men’s significant personal and interpersonal problems. In the middle of the paradigm, men’s defensiveness is shown and conceptually related to the many emotional, psychological, and interpersonal problems enumerated in Table 1. Men’s defensiveness is a key issue to consider when doing campus programming. Defensiveness and resistance are significant barriers for men to work through as they face the critical issues in Chickering and Reisser’s identity vectors. How to work with men’s defensiveness and unconscious sexism are challenging issues to resolve for service providers. Finally, negative emotions, such as anger, fear, guilt, anxiety, shame, self-hatred, hurt, loss and sadness result from this sexist gender-role socialization process and affect men’s developmental growth and identity development.

All of the masculinity issues on the top of Figure 1 have negative effects on the 7 identity vectors at the bottom of Figure 1. Patriarchy, sexism against men, gender role stereotypes, restrictive masculinity ideologies, distorted gender role schemas, GRC, and defensiveness all inhibit men from working on the identity vectors. Developing competence and managing emotions are difficult for a young man who experiences a restrictive gender roles and GRC. Autonomy, interdependence, and developing mature relationships are compromised when restrictive gender roles shape attitudes and behaviors during the college experience. Identity development and finding purpose in your life are difficult if you are distorting major gender role schemas and experiencing gender role conflict. Likewise, integrity is difficult to define and embrace if you are a prisoner to your sexist gender role socialization.

Student affairs workers can examine the utility of this paradigm in advancing any call to action for helping men. The cost are high for a college men who drop out of school, receive disciplinary actions or who commit acts of sexual and personal violence, including suicide. Furthermore, the great costs to women as victims need to be fully realized in the context of concepts in Figure 1. The paradigm is one way to conceptualize men’s problems and potentialities as well as a coherent way to justify expanded programming for college men.